Excellence is overrated

Why investing in top-stocks will not give you market-beating returns

In the 1980s, the market for high-yield bonds (aka junk bonds) experienced a dramatic boom. This was fueled by new deregulations in the finance industry and an increasing appetite for corporate takeovers. The junk bond market grew exponentially from a minuscule $10 billion in 1979 to a staggering $189 billion by 1989 - with yields averaging around 14.5%!

Unsurprisingly, given the market conditions and high inflation of the 80s, investors were drawn to these high-yield junk bonds. During this time, Ben Trotsky was a bond manager working for Pacific Investment Management Company (PIMCO). Even though he was deeply skeptical about junk bonds, he devised a brilliant strategy for investing in junk bonds that he called “Strategic Mediocrity.”

As a bond manager, he had to beat the benchmark to attract investors to his fund. This means he was competing with hundreds of other money managers who were playing the same game. They all got ranked from best to worst—every day, every year, every five years, and so on.

Ben decided that he never wanted to be first in a particular year — Anyone who ever got the No.1 rank almost certainly got it because they did something reckless, tried really hard, or took really big swings. They must have taken too much risk, and it worked out in their favor that particular year – but luck eventually runs out. When he did simulations of various long-term scenarios, everyone who showed up in the top slot eventually dropped out of the long-term rankings. But, if you stayed among the top 1/3rd consistently for a decade, you would be in the top 10% of fund managers.

That’s the beauty of Strategic Mediocrity. You never risk it all trying to generate the highest possible return in a given year. You play it safe, do well but not too well & try to be in the top 30% of the fund managers every year. That means not buying the scariest junk bonds that could have the biggest payoffs but going for one of the barely junk ones. While other fund managers were caught off guard by the collapse of the junk bond market in the late 80s, Ben was able to weather the storm and emerge as one of the most successful fund managers in history. PIMCO now manages more than $1.8 trillion in assets!

Michelle Clayman expanded this concept into businesses and had striking results. In her 1987 study, “In Search of Excellence: The Investor's Viewpoint,” she found that companies identified as “excellent” using traditional financial and business metrics underperformed “unexcellent” companies in the long run.

Defining Excellence

In their 1982 bestseller, In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Run Corporations, authors Thomas Peters and Robert Waterman, Jr. studied 62 companies to determine the characteristics of excellent companies. The companies were shortlisted by an informed group of businessmen, consultants, and academics.

A total of 43 companies passed all the criteria set by the authors and included blue chips like IBM, HP, Intel, Schlumberger, etc. (36 were publicly traded.)

The long-term financial superiority of these companies was assigned using six financial indicators (Based on a 5-year average)

Growth of total assets

Growth of shareholder equity

Return on sales

Return on average total capital

Return on average total equity

Year-end price to book.

What was striking was how these companies performed after being picked as excellent. Evaluating the performance of these companies over the next 5-year period, Michelle Clayman found that

86% experienced declines in asset growth rates

93% had declines in equity growth rates

83% had a lower average return on sales

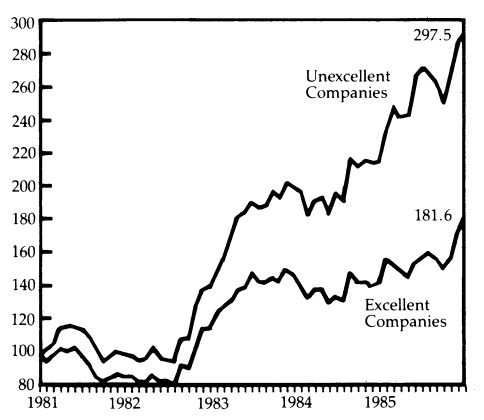

To add insult to injury, when Clayman evaluated the performance of “unexcellent” companies (by identifying 39 companies that had the worst combination of the six financial characteristics from the S&P 500), she found that an equally weighted portfolio of “unexcellent” companies returned 297% in 5-years compared to only 181.6% return of the “excellent” portfolio.

So, why did the supposedly excellent companies underperform?

Also, the astute among you may have noticed the time period of the analysis and will argue that the backtest was only done based on 5 years of data. So, does this trend hold for a longer period?

Let’s dig in: