The Fed Preview

Flying Blind

The Mirage of a Soft Landing

Upon his inauguration in 1969, Nixon inherited a recession from Lyndon Johnson who had spent generously on the social programs of the Great Society and the Vietnam War.

Despite some protests, Congress went along with Nixon and continued to fund the war and increase social welfare spending.

But President Nixon’s primary concern was not the U.S. dollar, or deficits, or even inflation. He feared another recession.

He and others who were running for re-election wanted the economy to boom. The way to do that, Nixon reasoned, was to pressure the Fed to lower interest rates.

Nixon fired Fed chair William McChesney Martin and installed presidential counselor Arthur Burns as his successor in early 1970.

In the winter of 1971, Fed Chair Arthur Burns made a decision that would haunt the American economy for a decade.

Under intense pressure from the White House to “juice” a slowing economy before the election, Burns cut interest rates.

He looked at a softening labor market and decided the war on inflation was effectively won. However, as Burns would come to realize, the cut was premature.

It felt like a victory at the time for the “soft landing” camp.

It wasn’t.

Inflation roared back aggressively, forcing the country into a punishing cycle of “stop-go” policy that eventually required a decade-long painful recession to fix.

This was also the period where the American economy entered ‘stagflation’.

Burns went down in history not as the man who saved the economy, but as the man who let the genie back out of the bottle.

History doesn’t repeat itself…

Fifty-four years later, Jerome Powell is staring down the exact same barrel.

As the Federal Reserve meets next week for the final time in 2025, the parallels are terrifyingly clear.

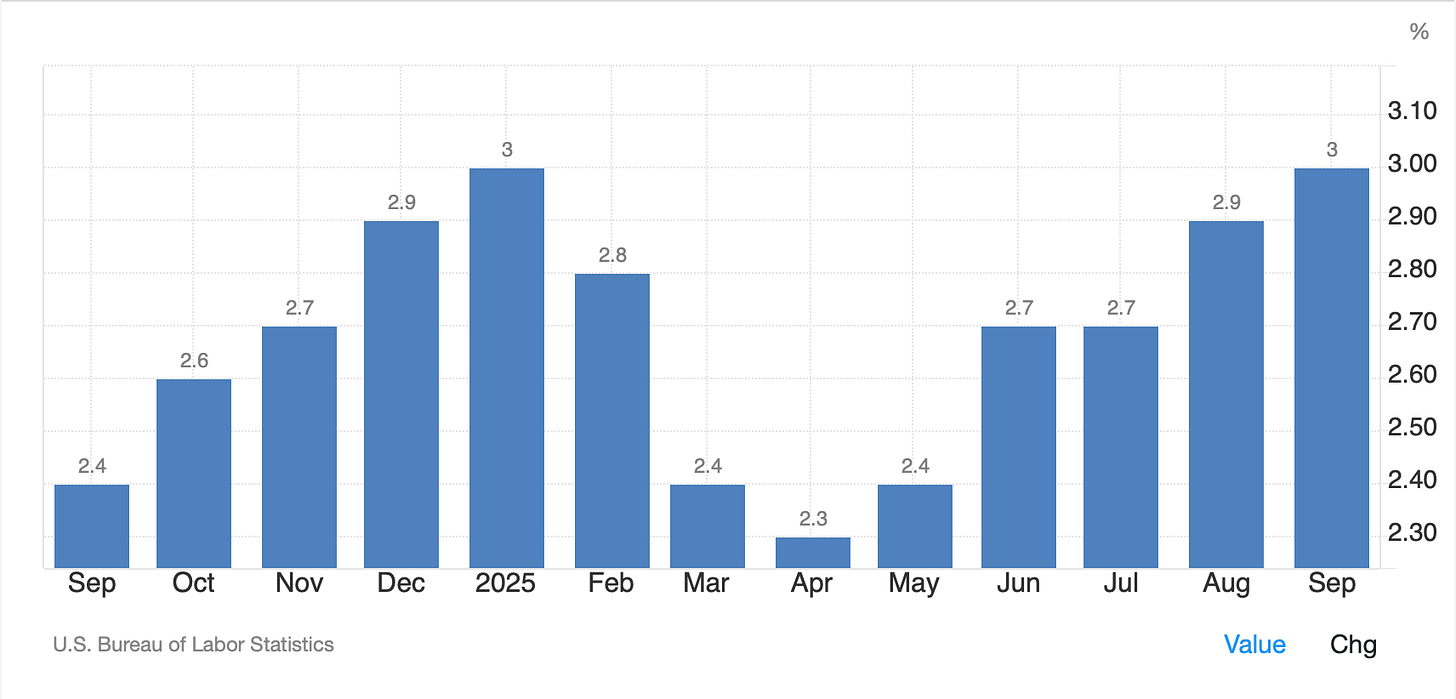

Inflation is sticky at 3%, stubbornly above the target, just as it was in the early 70s.

Unemployment is ticking up, just as it was then. And once again, a newly elected President is making his preferences for lower rates loudly known.

But Powell faces one danger that Burns did not: data, or the lack thereof.

Due to the recent government shutdown and the resulting data blackout, the Fed is about to make its most consequential decision of the post-pandemic era without a working instrument panel.

They are attempting to stick a soft landing while the runway lights are out.

Market Expectations

After lowering rates by 25 basis points in both September and October, Chair Jerome Powell has made it clear that another rate cut before the end of the year isn’t necessarily a given.

Yet, the market is clear on the direction it wants the Fed to take.

Traders are now pricing in an ~89% probability of a 25-basis-point cut next week.

However, this wouldn’t be a celebration cut; but a concern cut. The narrative has decisively shifted from “mission accomplished” to “prevention.”

The Fed essentially has two options:

The Fed’s Dilemma

The case for a cut

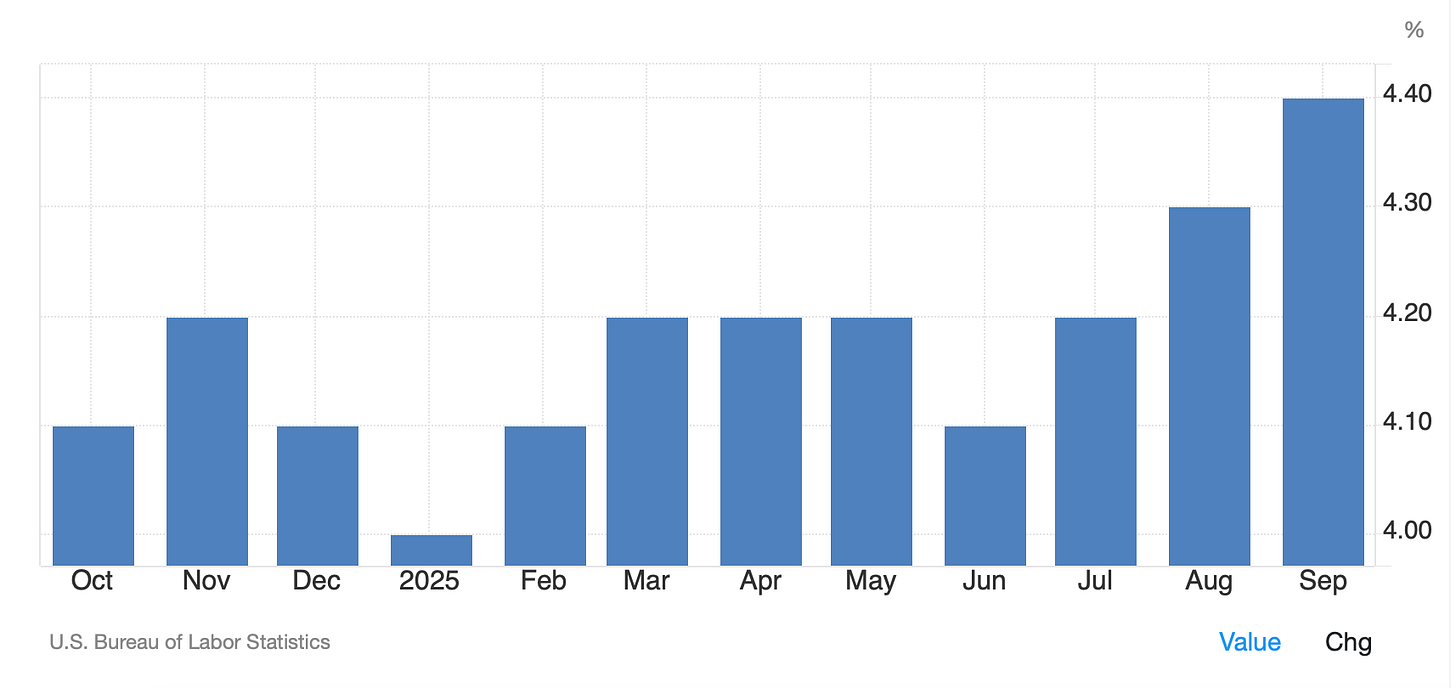

The Labor Slide: The unemployment rate has drifted up to 4.4% (from 4.3%), crossing a threshold that often signals a non-linear deterioration in jobs.

Anemic Growth: The Fed’s own projections (from the September SEP) forecast real GDP growth slowing to just 1.6% in 2025.

With growth barely above what’s normal, a rate cut acts as “recession insurance.”

Powell would likely rather cut early and risk slightly higher inflation than cut late and risk a full-blown employment crisis.

The Case for a Pause

Sticky Inflation: Core inflation remains stubbornly parked at 3%, a full percentage point above the Fed’s mandated target.

Easing financial conditions now could reignite the very fire they spent three years fighting.

Reducing inflation was the main goal of the quantitative tightening implemented in 2022, which has now ended as of December 1, 2025.

The Data Blackout: The strongest argument for a pause is the “fog.” Without the delayed October government data, easing policy is a gamble.

A pause would buy the Fed six weeks to see if the inflation is truly tamed or not.

The Fog of War: Navigating the Data Blackout

The recent government shutdown effectively cut off the access to information for the US economy.

For 43 days, the federal agencies responsible for measuring the country’s economic health, specifically the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), were largely empty.

Apart from several other implications, this also meant that essential data for federal policies was never collected.

The “Blackout” Mechanism Economic reports like the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or the monthly jobs report rely on thousands of human interactions.

Field agents physically visit stores to check prices, and call businesses to verify payrolls.

When the government shut down in October, those surveys never happened.

The Fed crucially operates on a principle of “data dependence.”

They adjust interest rates based on whether inflation is cooling or the job market is cracking.

Typically, they would have a clear picture of October and November to guide them. Instead, they are missing critical pieces of the puzzle:

Inflation (CPI/PCE): Without the October data, the Fed can’t be certain if the recent trend of cooling inflation has stalled or continued.

Employment: The October jobs report was cancelled. The Fed is effectively missing a month of insight into whether high interest rates are causing layoffs.

They are currently relying on “proxy” data from private payroll companies (like ADP) and anecdotal evidence, but these lack the precision of the official government numbers.

For instance, payroll processor ADP reported 42,000 new jobs added in October, exceeding both economists’ and Dow Jones’ expectations.

Yet data from Revelio Labs showed a loss of 9,100 jobs and a 37% surge in layoffs.

Challenger, Gray & Christmas revealed an even bleaker picture with job cuts spiking 183% in October to the highest monthly level in 22 years.

The risk of inconsistent data is policy error. Cutting rates too late because they didn’t see the job market crashing, or cutting too early because they missed a hidden spike in inflation.