The House Always Wins

Investing in Exchanges

Every market requires two things to exist: participants and a venue.

Stock exchanges serve as venues where transactions occur, security prices are determined, and capital is allocated. Here’s an interesting aspect about exchanges — they are basically Lindy companies.

Consider the S&P 500 — since its inception in 1957, only half of the originally listed companies have survived, while others were displaced by bankruptcy, mergers, or replacement.

Now contrast this against the exchanges:

New York Stock Exchange - 230 years old

London Stock Exchange - 220 years old

Toronto Stock Exchange - 170 years old

Bombay Stock Exchange - 150 years old

The New York Stock Exchange was born in 1792 under a buttonwood tree in New York City. What emerged from the informal gathering, the Buttonwood Agreement, was a pact to impose order and transparency on financial exchange. These merchants laid the groundwork for a controlled marketplace, where prices could be discovered fairly.

Over time, this pact evolved into an exchange worth over $30 trillion.

Today, there are approximately 60 stock exchanges worldwide, listing more than 50,000 public companies. While most companies struggle to survive a business cycle, exchanges have endured across centuries.

But what is it about the exchange that makes it immune to the tempests of the market?

Think of the exchange as a ‘contra-index equity class’. If the index goes up, the constituent stocks thrive. If the index sinks, there’s market carnage. But the exchange is agnostic to these movements. It’s monetizing ‘activity’ instead of market optimism. Whether participants want to buy or sell stocks, the exchange pockets spreads and fees and also benefits from rising volatility and transaction volume during periods of market chaos.

Another advantage of exchanges is their inherent adaptability. Despite market carnage or disruptors in an industry, the exchange still stands to win because it’s not betting on any outcome. Indices continue to rotate, and markets continue to go through bear-and-bull cycles. But whatever happens, everyone is paying rent at the exchange — short sellers, hedgers, speculators, passive investors.

Exchanges can scale unencumbered once the infrastructure is in place. They do not require proportionally more capital to support larger trading volume.

In addition, exchanges are positioned to capture new assets, financial instruments, or vehicles as markets evolve. Whether it’s obscure asset classes like Bitcoin or orange juice futures, the exchange has everything to offer as long as you’re willing to trade on the asset. If a new financial product comes into existence tomorrow, the exchange will list it and retain the fees, irrespective of whether the product succeeds or becomes a credit default swap case study for the books.

This leads to the more interesting question.

If exchanges profit from activity rather than market direction, should we expect them to outperform the very markets they host?

Market Sentiment delivers data-backed, actionable insights for long-term investors. Join 63,000 other investors to make sure you don’t miss our next briefing.

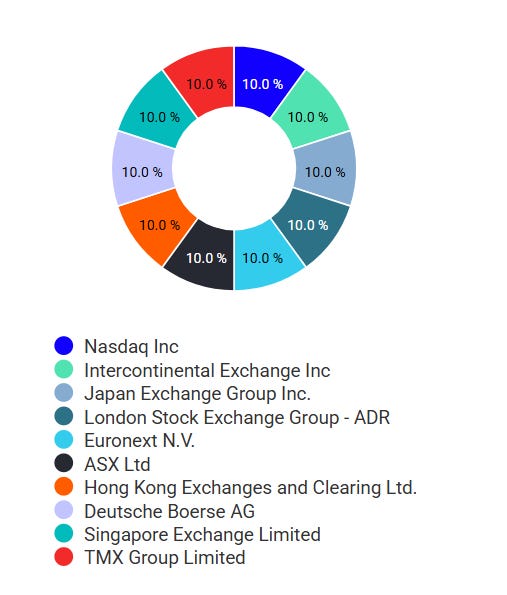

To test this hypothesis, we construct a global portfolio of exchanges and compare its performance to a portfolio of the indices they host.

NASDAQ and Intercontinental Exchange operate the two largest stock exchanges in the US: the NASDAQ and the NYSE, respectively. Euronext operates the major stock exchanges in 8 European countries. Japan Exchange Group owns the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Likewise, each exchange in the portfolio operates the primary exchange in its respective country.

For comparison, we consider a global portfolio of equity indices, mirroring the geographic allocations used in the exchange portfolio.