The Perils of Concentration

Risk is what you don't know you don't know

We are publishing this without a paywall.

In the late 1990s, the Janus Mutual Fund family was the talk of the town. The firm made its name as a growth-stock shop and had a popular fund called Janus Twenty. Unlike regular mutual funds that held 100s of positions, the Janus Twenty fund only had 20-30 of the best ideas of the fund manager.

This worked out really well during the dot-com bubble. The fund was heavily invested in Cisco, Worldcom, and Microsoft, and followed the mantra of growth at any cost. In 1998, the fund rose 73% and in 1999, it went up 65%. At one point in 2000, the fund was collecting $1B in inflows every day.

We all know what happened next.

The Dot-Com bubble burst, and Janus Twenty lost 69% of its value, eventually shutting down the fund. Adding insult to the injury, Enron was one of the largest positions of the Janus Fund.

While Buffett has made an immense contribution to the world of investing, one of the most damaging things he has ever said is his opinion on portfolio diversification.

You know, we think diversification is — as practiced generally — makes very little sense for anyone that knows what they’re doing. …

Diversification is a protection against ignorance. ….

I mean, if you look at how the fortunes were built in this country, they weren’t built out of a portfolio of 50 companies. They were built by someone who identified a wonderful business. Coca-Cola’s a great example. A lot of fortunes have been built on that.

Here’s the funny part — Buffett had a concentrated position in Coke as of 1996, which he has maintained to this day. Since 1996, the S&P 500 has outperformed Coke by 2.5X!

Finally, for all the talk about concentration, Berkshire Hathaway owns 70+ companies and has 50+ stock positions.

Market Sentiment delivers data-backed, actionable insights for long-term investors. Join 56,000 other investors to make sure you don’t miss our next briefing.

Behavioural aspect behind diversification

If you follow the stock market daily, you will encounter an interesting behavioral economics phenomenon called loss aversion. It’s where a loss is emotionally more severe than an equivalent gain. For instance, the pain of losing $100 is far greater than the joy gained in finding the same amount.

Based on the loss aversion theory, if we assign a +1 happiness score if the markets end in green and a -2 if the markets end in red (The 1:2 ratio is often considered the thumb rule), we see that someone who checks the market daily will be deeply unhappy — irrespective of their overall gains.

Given how unhappy you can be with a winning asset like the S&P 500, you can imagine how much regret you will have while holding a loser.

Performance of concentrated portfolio managers

Great fortunes have been created by visionaries who seized a unique opportunity and work singlemindedly to realize their ambition. Concentration is an effective engine of wealth creation: In the US, the top 10 of the “Forbes 400” also made their fortunes through concentration.

As difficult as it is to build a company and amass wealth, it is just as difficult to keep fortunes aloft. Our analysis (and others before it) demonstrates the hard reality that, all too often, continued concentration may ultimately destroy wealth.

It’s a common misconception that a concentrated portfolio improves returns. Increasing portfolio concentration also increases the risk of missing out on some of the market’s big winners. In addition to this, the most common reason for a business failure was outside management’s control.

Read that again — The most common reason why a business went bankrupt was not due to management inefficiency, but due to factors outside their control.

JP Morgan found that more than 40% of the companies in Russell 3000 experienced a catastrophic stock price loss (70%+ decline in stock price) and that the median return for an individual stock in Russell 3000 was negative.

A manager who has a concentrated portfolio is statistically more likely to pick a stock that underperforms the market.

According to Morningstar research, there is no statistically significant outperformance from mutual funds that have a concentrated holding.

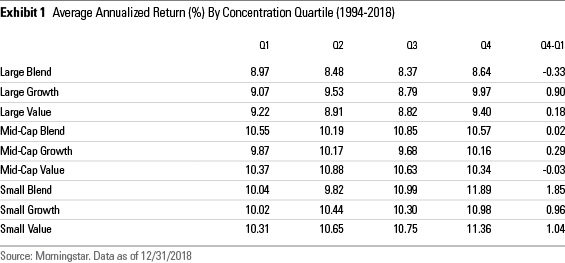

The most-concentrated quartile of funds (labeled Q4) generated higher annualized gross returns than the least-concentrated quartile (Q1) in seven of the nine U.S. equity categories from January 1994 through December 2018.

Similarly, the most-concentrated quartiles posted higher returns in five of the six foreign stock categories from 2004 through 2018. However, none of the return differences between the most- and least-concentrated quartiles were statistically significant.

Survivorship Bias

It’s interesting how an active fund becomes popular - For this, a fund has to achieve “orbital velocity”. What usually occurs is that you start with a few million dollars, you make some high-risk bets that work out in your favor, and suddenly you have a fund that outperforms the market.

The market usually evaluates 3 to 5-year performance and if you made the bets at the right time and with a bit of luck on your side, you are suddenly the hot new fund in the market. With the help of a couple of skilled marketers, you can easily pull in a few billion into the fund.

What everyone is missing is all the funds that never made it. Just look at the data — In the first half of 2024, 93 new mutual funds were launched, but 123 shut down. No one looks at the performance or reasons for the funds that shut down.

ARKK is the best example of a fund that “made it”. The fund barely had a billion under management at the beginning of 2019. The company made some massive bets on tech companies such as Zoom, Tesla, and Coinbase, and they paid off incredibly well during the rally just after the pandemic. Investors piled onto the fund and at its top, it had close to $30B under management - a 30x jump in just 3 years.

By the end of 2023, the ARK fund was at the top of the list of the most wealth-destroying funds of the decade.

The ARK family wiped out an estimated $14.3 billion in shareholder value over the 10-year period—more than twice as much as the second-worst fund family on the list. — Morningstar

Verdad Research simulated fund returns, removing survivorship bias, and found that hyper-concentration doubles a manager’s risk of generating the target return.

Based on data of US stocks from S&P Capital IQ, we simulated 10,000 manager portfolios at levels of concentration that ranged from 5 stocks to 500 stocks.

Every manager in the simulation invests their portfolio with annual rebalancing over a 10-year horizon. This setup fully avoids survivorship bias as no manager drops out of the simulated database.

The unranked portfolios show that hyper-concentration doubles a manager’s risk of falling short of their LPs’ 5% minimum return target over 10 years. Portfolios of 5–10 stocks have a ~40% chance of returning less than 5% annualized over 10 years, whereas the shortfall risk for unranked portfolios with more than 50 stocks is roughly 20%.

It’s important to note that the probability of shortfall begins to stabilize at around 50 stocks and remains about the same, all the way out to 500 stocks.

The allure of concentration

The simple reason why concentration is so attractive is that others make it look like you could have also done it. Take the example of Jason Debolt.

He started purchasing Tesla stock in 2013, buying 2,500 shares at $7.50 per share. He kept adding over the next 7 years, and by 2021, he had 14,850 shares. Then he made this post that went viral.

He continues to hold the stock and is so bullish that, in his opinion, he will go back to work to avoid selling the shares.

My ultimate goal is to avoid selling any TSLA shares, even if I have to go back to work. I plan to finance retirement with a margin loan at a less than 1% interest rate.

But for each Jason out there, there are hundreds of others who chose the wrong stock.

(including some of the most famous investors)

I’m extremely comfortable with the Wirecard investment. I might remind you I invest in companies — not stock — and the point about Wirecard is: it’s a great company. — Alexander Darwell (Wirecard dropped 98%)

The biggest regret I have with Valeant is that we’re not in a position to buy more — Bill Ackman (Valeant eventually fell 93% from its peak)

Diversification is hard because there will always be something in your portfolio that underperforms. This is a feature, not a bug.

NASA calculates the number of single-point failures for every mission. It’s the part or process of a system that, if it fails, will stop the entire system from working. The idea is to minimize the number of single-point failures and to keep redundancies where the risk is the highest. Similarly, we should always evaluate our portfolios for weaknesses.

After all, putting all the eggs in one basket has rarely worked out for anyone in investing.

Further Reading

Concentrated portfolio managers: Courageously losing your money — Acadian

Total Concentration — Verdad Research

Great write ups on such an important topic. The quotes from legendary investors that went all in on fraudulent businesses really brings the point home.

That’s why index fund/etf investment makes sense: diversification and automatic elimination of losers.