Bigger Slice of Pie

Buybacks: Show of confidence or stock manipulation?

Welcome to the 500+ investing enthusiasts who have joined us since last Sunday. Join 31,300+ smart investors by subscribing here. It’s totally free :)

Check out our - Best Articles | Twitter | Reddit | Discord

Sponsored by Masterworks

Microsoft Co-Founder’s $1.6B+ Sale Highlights “Safe Haven” Asset

Just last month, Paul Allen’s historic art collection shattered the record for the largest-ever sale in auction history.

The fact that the blue-chip art market is still setting records amid major drawdowns in financial markets, and macroeconomic turmoil, highlights why it can be such a strong alternative diversifier. In fact, the high-end art market also remained resilient through downturns like the dot-com bubble and Great Financial Crisis.

But this time around, it’s not just the ultra-wealthy benefitting.

Thanks to Masterworks. This unicorn investment platform allows everyday people to invest in shares of multi-million dollar art by names like Banksy and Picasso. So far, seven of Masterworks’ last eight exits have realized a net return of +17.8%.

Market Sentiment readers can skip the waitlist with this referral link.

See important Regulation A disclosures.

“Henry Singleton of Teledyne has the best operating and capital deployment record in American business.”

- Warren Buffett

Henry Singleton’s origin story is great. But his comeback is even more fascinating.

Singleton and his partner founded Teledyne Technologies in 1960 using an initial investment of $450,000 with the vision of establishing a large firm focused on semiconductors and digital devices. Within 9 years, Teledyne had sales of $1.3 Billion and a net income of $60 million - A 133x return on the initial investment. Taking advantage of Teledyne’s high PE ratio, Singleton acquired close to 150 companies in this period, making it the most successful conglomerate of the era - till the end of the 60s, when the conglomerate bubble burst. Teledyne’s stock collapsed from $40 to less than $8. But Singleton’s second round was even more remarkable than the first.

Singleton took advantage of Teledyne’s undervalued stock price and decided to go on a buyback spree. It was an unusual move for the times and he was advised against it, but he went ahead and used multiple tactics, including tender offers and Dutch auctions, to buy back more than 90% of the outstanding shares from October 1972 to February 1976. By the end of the decade, the stock price rose to $175. By the time Henry retired in 1991, the stock price was $338. Shareholders who bought in during the bubble burst and held on would have gained 4,125% - a 19.5% annual return.

Stock Buybacks were not new, but dividends had been the dominant mode of returning shareholder value till then. Starting from the 80s though, buybacks have become the major option for corporates to pay out shareholders. Buybacks have been the single largest source of US equity demand each year since 2010, averaging $421 billion annually.1

How do buybacks work, and can you use them to identify better investments?

How do buybacks work?

Imagine a company that is valued at $100 Million, with 1 Million shareholders. Each shareholder’s stake is worth $100. If the company has a Free Cash Flow (FCF) of $5 Million this year, it has three ways to use that money:

It can find new ways to reinvest in the business

It can pay out a dividend of $5 to each shareholder

It can “buy out” 5% of the shareholders with the excess money

There is no immediate benefit to buying out the shareholders, but in the next year, the profits will be distributed to a smaller number of people and each remaining person’s slice will be worth more.2 Instead of returning capital as money by paying out dividends, a company can choose to reward loyal shareholders by increasing the value of the shares they hold.

Let’s try a thought experiment. A company’s FCF grows by 10% every year. Its stock is a fixed multiple of the FCF per share. The company has two options: To buy back 5% of its shares every year, or to do nothing. This is how the stock price would differ over 10 years.

In 10 years, the profits with buybacks would be more than 2x the profits without buybacks! Of course, this is an oversimplification. When companies buy back their shares, they will affect the public perception of the share, and share buybacks are not annual affairs like dividend payouts. Still, this is a useful comparison to understand the power of buybacks.3

Buyback returns

When companies repurchase their shares on the market, it could indicate favorable long-term prospects for the company by signaling that the shares are undervalued. Investing in companies that execute large buybacks is one possible strategy. The S&P 500 Buyback Index does exactly this - It tracks the top 100 companies in the S&P 500 by buyback ratio. Since its inception in 2012, it has recorded a 315% return compared to the S&P500’s 278% (an annualized return of 12.05% vs the S&P500’s 10.74%).

There are more nuanced approaches as well. In his book “What works on wall street”, Jim O’Shaughnessy proposes a metric called “Buyback yield” which measures the change in outstanding shares of a company in the market over one year. The theory is that if a company is buying back its own shares, it believes its stocks are undervalued. If the buyback yield is negative, then the company believes its stocks are overvalued and is diluting its stock by issuing more.

Let’s look at the strategy applied to Large Cap stocks4 from January 1926 to Dec 2009, the results are as follows:

The cumulative returns from the strategy are 1158 times that of the benchmark over 83 years. The strategy outperformed the benchmark in 85% of all rolling five-year periods and 88% of all rolling ten-year periods. The caveat is that there is substantial risk associated with the strategy: There were seven separate times when the Buyback portfolio would have dipped by 20% or more, and it dipped by 53% during the Great Financial Crisis. The strategy does not offer protection against market drawdowns.5

But we get another interesting insight when we rank stocks by their buyback yield and see what happens to the stocks in the lowest decile (the ones that issue shares instead of repurchasing them). In the figure below, deciles 1 to 5 are companies that buy back shares, 6 and 7 are companies with no activity, and 8 to 10 are companies that issue shares.

Companies that buy back shares outperform the market, as expected. But the most glaring takeaway from the above image is what happens in deciles 9 and 10. Companies that issue new stocks and have the lowest buyback yield have a terrible performance relative to the benchmark. Over 83 years, a 4.6% difference in annual compounded returns is huge! Avoid companies that dilute their stocks at all costs.

A major advantage for buybacks compared to dividends is the tax angle. Dividends are taxable during payout at standard Federal Income rates that can go up to 37%, but buybacks have a much lower capital gain tax that needs to be paid only when the shares are sold. This lets your returns compound at a higher rate.

The dark side

If buybacks seem like they are too good to be true, it’s because the controversial aspects have not been discussed so far. A major portion of compensation for corporate executives is tied to the performance of the stock, and there are opinions that buybacks can artificially boost the price of stocks in the short term so that executives can exercise their stock options. In 1982, Rule 10B-18 was introduced by the SEC which provided a “safe harbor” to executives as long as they met certain conditions regarding timing and volume.6

While there is some truth to this idea, it is not as simple as it’s made out to be. Conditions like vesting stock options over a longer period of time can align the incentives of executives with shareholders. As Chris Meredith writes, “Trust but verify.” Buybacks should be used in combination with other metrics such as earnings growth and accruals to judge the financial growth of a company.

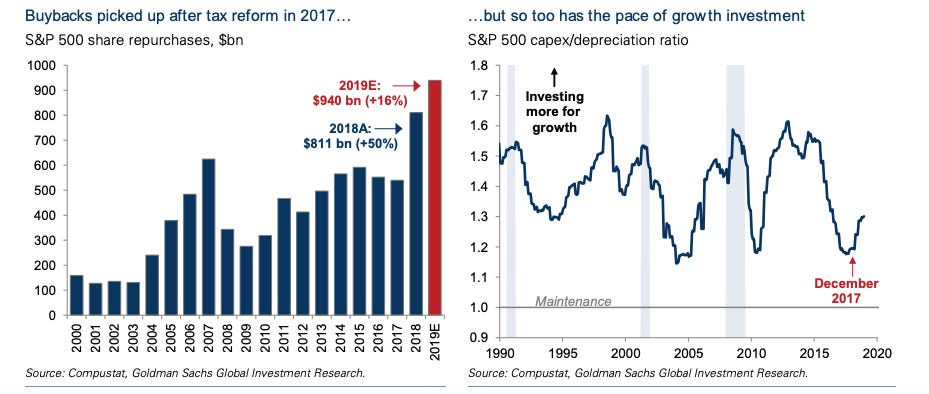

Another criticism is that buybacks signal that the company is out of ideas to invest in new projects and would lead to a decline in its prospects soon. Apple is an oft-cited example of this. But here too, the picture is only partially correct. Buyback payouts have gone up in the past decade, but so has capital invested into growth and R&D. As Buffett said, “I’m not aware of any enticing project that in recent years has died for lack of capital. (Call us if you have a candidate.)”

So in which scenarios are buybacks a good idea?

Stock buybacks have a close relationship with how shareholder payouts have evolved with time. In the days of Ben Graham, stocks were seen as an alternative to bonds, so dividend payouts were modeled to operate like bond yields. But the problem with dividends is that they set an expectation for regular cash flow that worked for businesses of the past, but might not sync with modern companies.

Buybacks are more flexible. They offer a way to reward loyal shareholders, align incentives of executives, and pay shareholders with excess cash without committing to an indefinite schedule. When combined with other financial health and value metrics, they are a good indicator of a company’s long-term prospects and a way to get a bigger slice of pizza without paying extra for it.

Do you think buybacks are a poor use of capital? Let me know in the comments below.

More interesting finds

I have been obsessed with OpenAI’s ChatGPT over the last week. It answers questions in any domain and is a great way to do research and have some fun. In fact, the preliminary research for this article started in the form of a chat with the AI, and it pointed me in some interesting directions. Check it out - It’s free to try!

What operators can teach investors: This talk between LibertyRPF and Cedric Chin dives deep into how to identify patterns in domains like business and investing. It also has a great contrarian take on why thinking from first principles might not be the only valid approach.

If you enjoyed this piece, please do me the huge favor of simply liking and sharing it with one other person who you think would enjoy this article! Thank you.

Disclaimer: I am not a financial advisor. Please do your own research before investing.

In comparison, during this period, average annual equity demand from households, mutual funds, pension funds, and foreign investors was less than $10 billion each.

Theoretically speaking. It can take quite some time for this to reflect in the share price, but the value of Earnings per Share will increase as a result of the buybacks as long as the company’s financials are sound, and perceived value will increase in the long run.

For more on how buybacks work and how the different variables affect the stock price, check out this excellent thread by 10k-diver.

The benchmark considered here is not the S&P 500 (market cap weighted), but rather an equal-weight average. The strategy also works with respect to mid and small-cap stocks and you can check out the book for the analysis.

The research methodology used by O’Shaughnessy is detailed here. The book also consolidates methods that have the lowest downside risk by combining Buyback Yield with other factors like Dividend Yield.

There are even strong opinions that open market buybacks should be banned. This is a political topic that has arguments on both sides.

used to have access to Bloomberg which I am sure would offer query for that. I wonder if ChatGPT could solve along lines of "largest percentage decline in diluted shares outstanding over past X years for members of <examined index>"

thanks. It's on my lost to examine. Have seen some fairly interesting uses of the capability already.