If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants — Isaac Newton

A relatively little-known fact is how much of a role Nobel Laureate economist Paul Samuelson played in the creation of the index fund. While John Bogle hinted at the idea of an index fund in his thesis at Princeton University way back in 1951, it was Dr. Samuelson’s challenge in the Journal of Portfolio Management (1974) that gave John the much-needed confidence to take on the industry.

Samuelson laid down an express challenge for somebody, somewhere to start an index fund.

That, at the least, some large foundation set up an in-house portfolio that tracks the S&P 500 Index-if only for the purpose of setting up a naive model against which their in-house gunslingers can measure their prowess

The American Economic Association might contemplate setting up for its members a no-load, no-management-fee, virtually no-transaction-turnover fund.

Bogle took up the challenge and his company The Vanguard Group launched the first index fund in 1976 — The rest is history.

This is just one example of academic research being years ahead of industry. In 1982, Rolf Banz published a report that showed that small stocks had consistently higher average risk-adjusted returns that the efficient market hypothesis could not explain— A trend that exists to this day1 (Since 1990, small-cap stocks have outperformed large-cap stocks by 45%). Momentum strategy was identified more than 30 years ago2 and it has beaten the market consistently and the trend has held in 40 different countries over 12 different asset classes3.

Following academic research is the key to staying informed about emerging trends and innovative investment strategies. What we have found from our last 3 years of exploration is that identifying academic developments early can give investors the much-needed competitive edge to create alpha-generating strategies that are not yet mainstream.

But, this is easier said than done. There are 64 million academic papers published since 1996 and ~5 million articles that are being added every year. Keeping up with the latest developments in their own field is challenging for seasoned academicians.

So, starting this week, in addition to our deep dives, we will be curating a list of the most impactful and interesting developments in the investing space from academia. You can vote on what you thought was the most interesting one at the end and we will do a comprehensive deep-dive on it.

Before we jump in, here is Charlie Munger on how he made $500m from reading finance magazine Barron’s4:

I read Barron’s for 50 years. In 50 years, I found one investment opportunity in Barron’s. I made ~$80m with almost no risk. I took the ~$80m and gave it to Li Lu, who turned it into $400-500 million.

So I have made $400-500 million from reading Barron’s for 50 years and following one idea.

1. Can ChatGPT Forecast Stock Price Movements?

Alejandro Lopez-Lira & Yuehua Tang (University of Florida) — Full paper (open access)

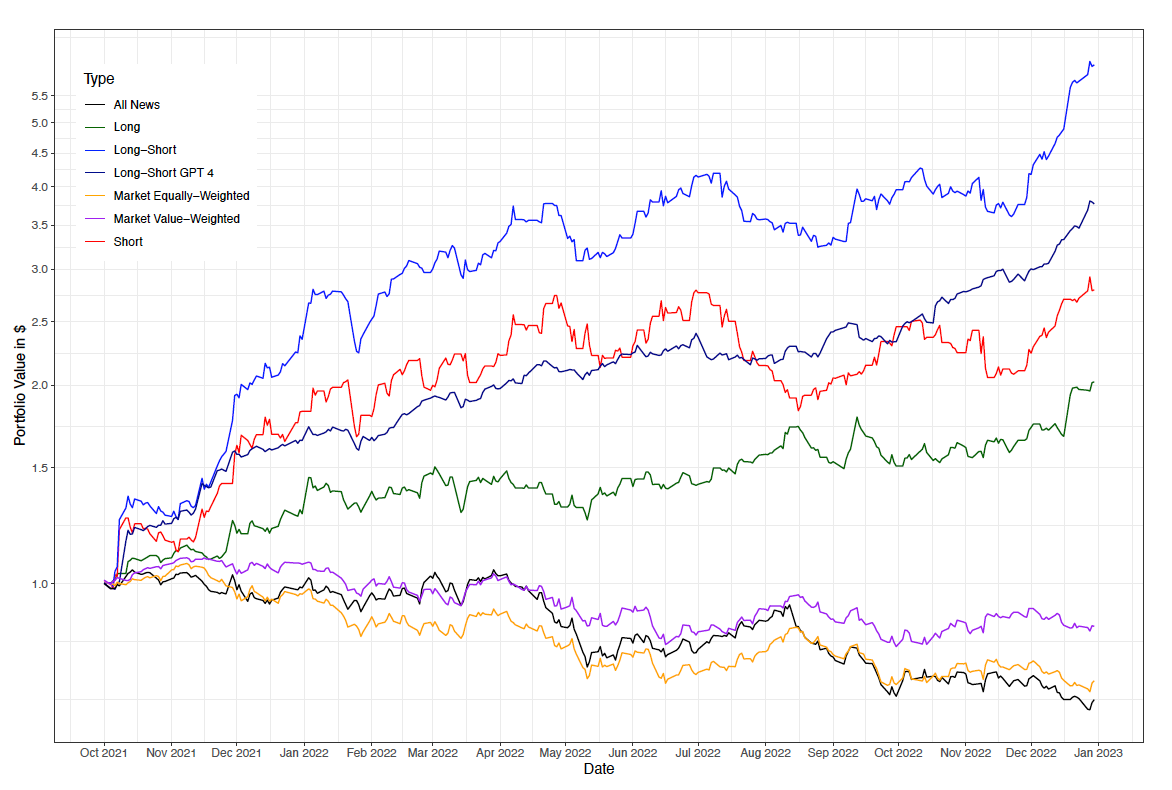

In this, the authors tried to answer the question that’s on all of our minds. They prompted ChatGPT to pretend to be a financial expert and to respond with yes, no, or unknown to the question of whether a particular headline is good or bad for a company.

Based on the average score using all available headlines against each company, they built a simple long-short strategy that buys stocks with a positive score (aka positive sentiment) and sells stocks with a negative score. The results were stunning:

Ignoring the transaction costs, a long-short strategy on ChatGPT-3.5 returned 550% from 2021 Oct to 2022 Dec with both the long side delivering 200% and the short side delivering 250% (during the same period, the S&P 500 was down ~10%!)

2. A Sober Look at SPACs

Michael Klausner, Michael Ohlrogge, Emily Ruan — Full paper (open access)

If there was one thing most investors should have read in 2020, it should have been this. During the bull run of 2020-21, more than 861 SPAC IPOs occurred in the U.S. (compared to the less than 20 per year average over the past decade). Chamath Palihapitiya was the SPAC poster boy and he was even called the next Buffett (he even compared his fund’s performance to Buffett’s).

Almost all of his SPACs underperformed the market with some losing up to 95% of their value. But, by selling most of his shares early, he roughly doubled the $750 million he put in while small investors were left holding the bags.

The authors calculated the staggering total costs associated with a SPAC deal — For all the SPACs that merged from Jan 2019 to Jun 2020, the mean total costs as a percentage of pre-merger equity was 58%!

That means that a SPAC share worth $10 only has $4.10 net cash per share at the time of the merger. They also found that post-merger, the company share price declined in proportion to the pre-merger net cash — Meaning long-term SPAC holders ended up bearing all the costs.

We find that SPAC costs are not borne by the companies they take public, but instead by the SPAC shareholders who hold shares at the time SPACs merge. These investors experience steep post-merger losses, while SPAC sponsors profit handsomely.

3. Why do equally weighted portfolios beat value-weighted ones?

Alexander Swade, Sandra Nolte, Mark Shackleton, and Harald Lohre — Full paper (open access)

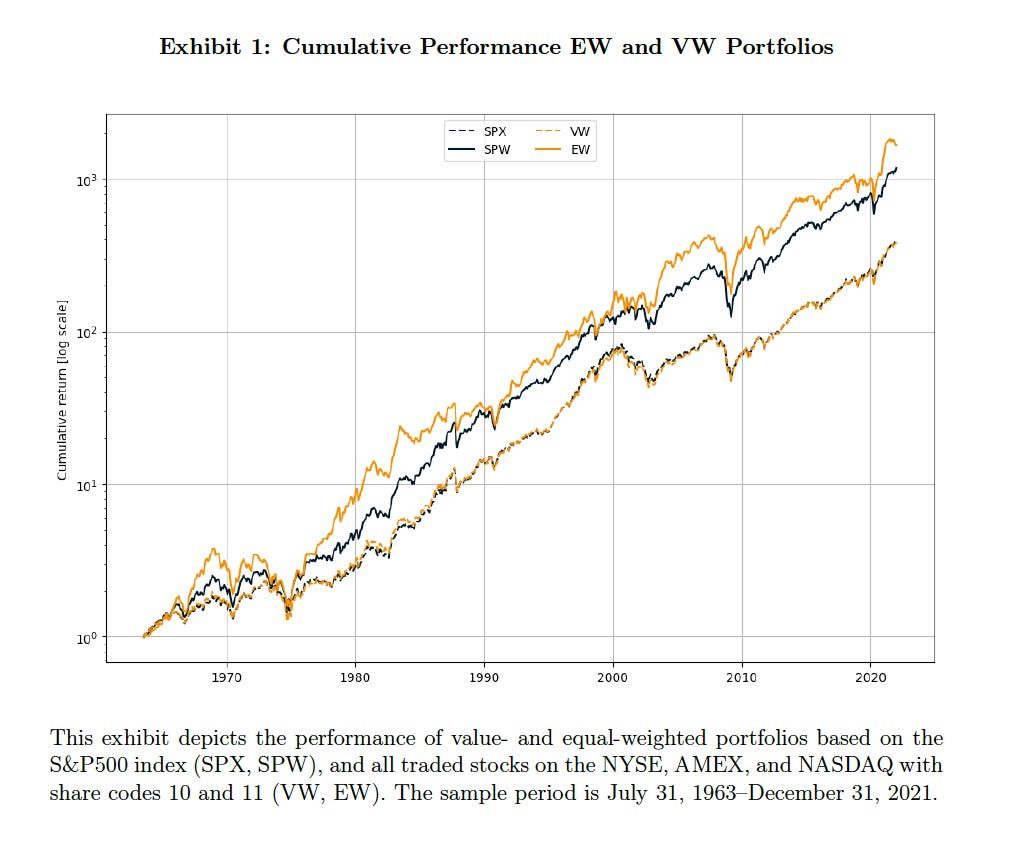

A vast majority of index funds and ETFs are value-weighted. As the companies become more valuable, more capital is allocated to them. The top 5 companies (1%) of the S&P 500 contribute close to 22% of the total S&P500 market cap.

Based on existing research5, equal-weighted portfolios have consistently outperformed their value-weighted counterpart. The key reason for the outperformance as found by the authors was that by design, the equal-weighted portfolio overweight into small-cap companies (thereby activating the size premium).

They also found that equal-weighted portfolios tend to perform better when there are short-term trend reversals in the market (As we are focused on selling winners and buying losers in an equal-weight strategy) but suffer from a negative momentum exposure.

4. Can commodities add the necessary diversification to portfolios?

Vianney Dequiedt, Mathieu Gomes, Kuntara Pukthuanthong, and Benjamin Williams-Rambaud — Full paper (open access - preprint & not peer-reviewed)

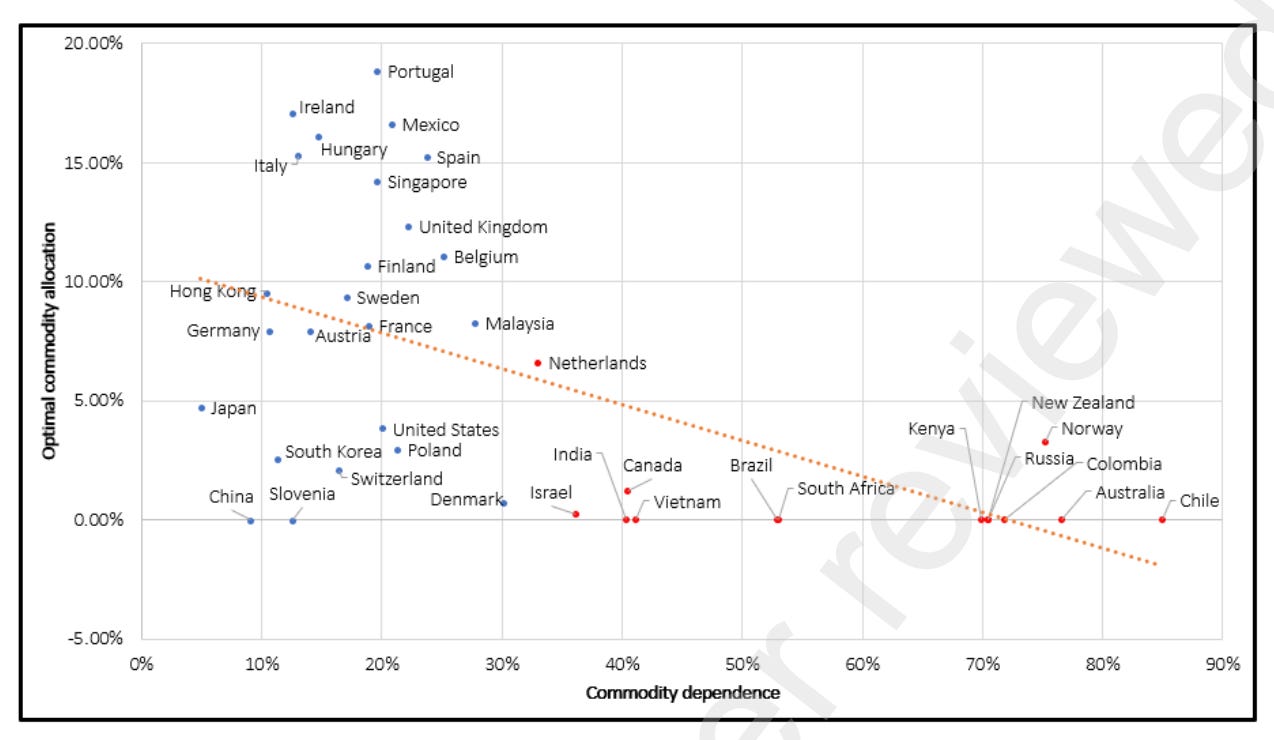

The study investigated the diversification benefits provided by commodities across 38 different markets. While commodities are usually considered to add diversification benefits to the portfolio6, the authors found that the diversification benefits depend on how much the investor country is dependent on commodities.

Specifically, we establish that investors in high-commodity-dependent countries generally do not accrue benefits from adding commodities to their portfolios. In contrast, those located in low-commodity-dependent countries typically do.

Whether and how much to add commodities to your portfolio is a function of your country’s dependency on commodities. Investors in countries like Brazil, Russia, Australia, etc. who have high dependency on commodities do not tend to benefit by adding commodities to their portfolios.

5. International diversification is still important for U.S. investors

Cliff Asness, Antti Ilmanen, and Dan Villalon (AQR) — full paper (open access)

AQR research recently published a report in which they argued that the U.S. outperformance was mainly driven by valuation changes rather than fundamental improvements in the economy (emphasis by author)

Since 1990, the vast majority of the US’s outperformance versus the MSCI EAFE Index (currency hedged) of a whopping +4.6% per year, was due to changes in valuations.

The culprit: In 1990, US equity valuations (using Shiller CAPE) were about half that of EAFE; at the end of 2022, they were 1.5 times EAFE. Once you control for this tripling of relative valuations, the 4.6% return advantage falls to a statistically insignificant 1.2%.

In other words, the US victory over EAFE for the last three decades—for most investors’ entire professional careers—came overwhelmingly from the US market simply getting more expensive than EAFE.

Almost everyone considers the U.S. to be the best market, which in turn pushes the prices of securities upward. As value investing teaches us, winning simply because the other person is willing to pay more is not a sustainable strategy.

If you found this recently, the poll is closed. Here is the deep-dive:

Data, references, and footnotes

Fama eventually explained this outperformance using the small firm effect in the Fama-French three-factor model.

Returns to Buying Winners and Selling Losers: Implications for Stock Market Efficiency (Narasimhan Jegadeesh and Sheridan Titman)

Value and Momentum Everywhere — Asness, Moskowitz, and Pedersen (2013).

Trung Phan recently published a great piece on how most successful founders love reading

The data show risk-adjusted returns for a diversified stocks and commodities portfolio outperformed over the entire period of study (since 1/31/1970) when compared to commodities or stocks alone. — Washington Trust Bank

Just a reminder that Market Sentiment is now fully reader-supported. A lot of work goes into these articles and if you enjoyed this piece, please hit the like button and consider upgrading your subscription to get access to all issues.

Great post. Thanks.