Lessons from Warren Buffett

What made Warren Buffett Warren Buffett

Market Sentiment delivers data-backed, actionable insights for long-term investors. Join 48,000 other investors to make sure you don’t miss our next briefing.

We are publishing this without a paywall.

At Berkshire’s shareholder meeting this weekend, Buffett announced that he will retire at the end of the year and Greg Abel will take over as the chairman of Berkshire Hathaway.

Buffett is arguably the greatest investor we will ever see. To put his performance in context, Berkshire could drop 99% today, and you would still have outperformed the market if you started with Buffett in 1964.

$100 invested with Buffett starting in 1964 would have now grown to over $5.5 million compared to $39K in the S&P 500. Buffett did this while having the highest Sharpe and Information ratios of any comparable company or mutual fund.

Since the chances of another Buffett coming in our generation are slim to none, here are five lessons on what made Warren Buffett Warren Buffett.

The magic of float

Buffett spent a lot of time developing the optimal structure for his investments.

Till the late 1960s, Buffett ran his partnership with a performance fee till he shut down his fund, stating that he couldn’t find any rational opportunities. But Buffett continued investing through the vehicle that he is most famous for today – using the holding company of Berkshire Hathaway.

Berkshire was a publicly traded company and not a fund, so it freed him from some fiduciary duties and allowed him to reallocate capital as he saw fit. However, through Berkshire, Buffett acquired insurance companies like Geico, National Indemnity, and General Re.

This gave Buffett access to float, one of his favorite tools.

As Marc Rubinstein explains here, Buffett’s insurance company acquisitions gave him access to billions of dollars in float – the difference between the regular premiums paid by policyholders and the due claims.

Even when the insurance company was unprofitable, the delay in resolving claims meant that the float was available for reinvestment at low costs, and in profitable years, the cost was even negative.

Float and excellent credit ratings gave Berkshire access to cheap financing that helped Buffett leverage good investments by a ratio of 1.4 to 1.71. You don’t need to be a genius to understand the power of leverage applied correctly.

Investing in companies with an enduring moat

One of our personal favorites from Berkshire’s portfolio is FlightSafety. The company was started in 1951 and provides flight training for pilots. Berkshire acquired FlightSafety in 1996 & Buffett argued that it had one of the best durable competitive advantages: Being a pilot is a highly skilled job, and there is no room for error. Anyone who wishes to be a pilot would like to be trained by the best, and FlightSafety is arguably the best flight-training provider.

In Buffett’s own words

Going to any other flight-training provider than the best is like taking the low bid on a surgical procedure.

This is not just vibe-based — established research highlights that wide-moat companies outperform the market and provide better downside protection during the inevitable market downturns.

Infinite holding period

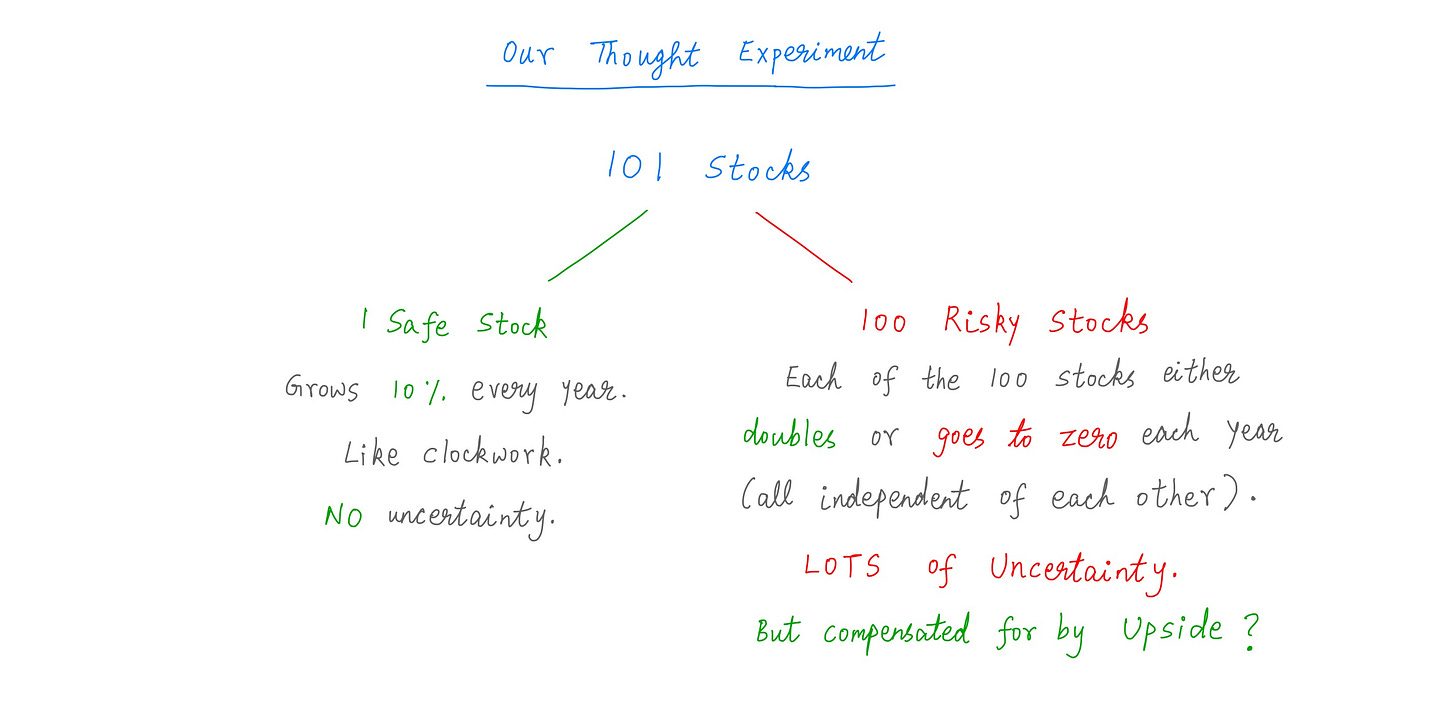

Here is one of my favorite thought experiments, which shows that survival over the long term is much more important than higher short-term returns.

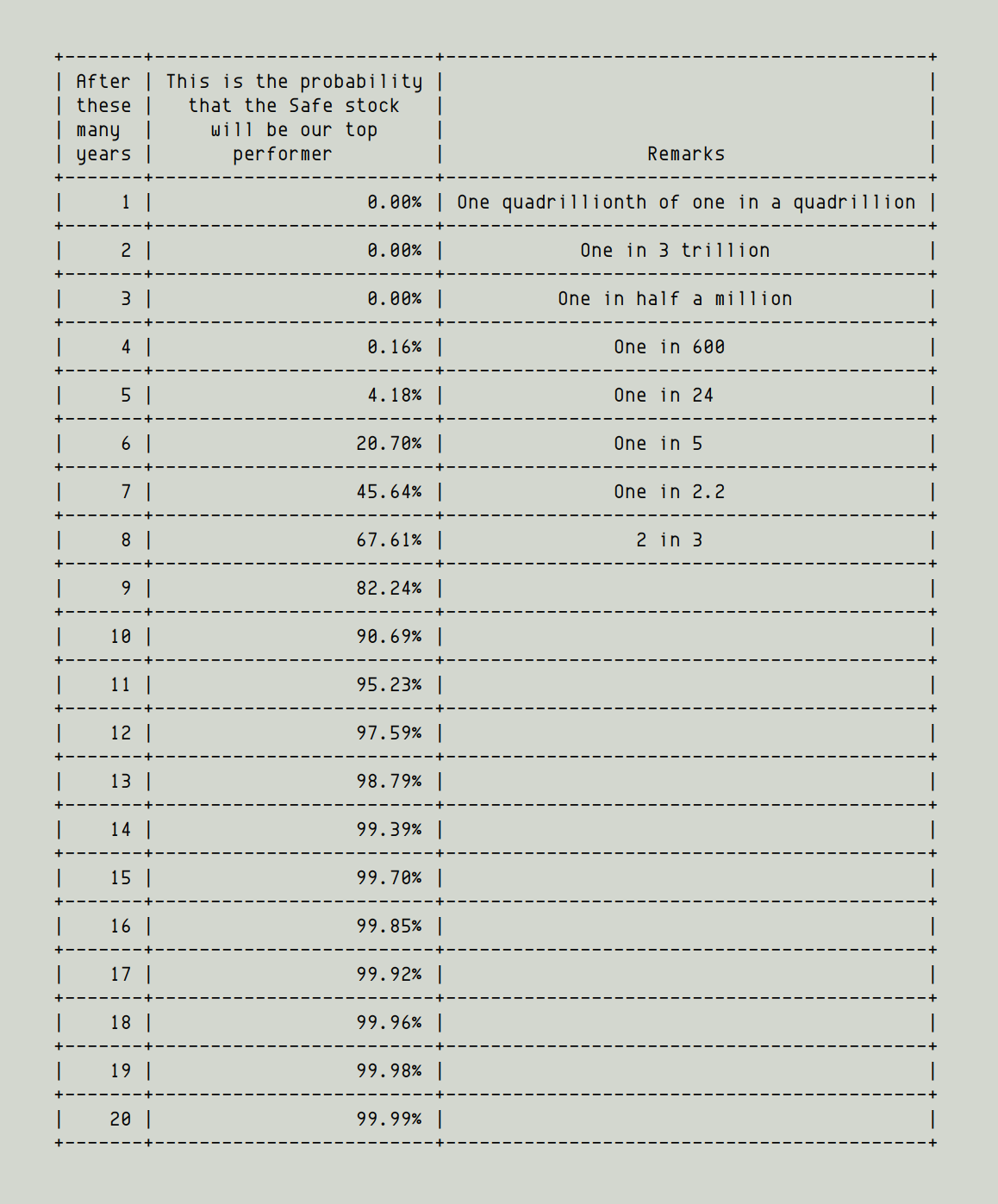

Out of these two options, which one do you think would be the better choice in a few years? In the first few years, our safe stock underperforms the risky stock, which doubles in value yearly.

But as time goes by, the risky stocks start dropping off. After 10 years, there is a 90% chance that the safe stock will be the top performer, and after 15 years, it’s virtually guaranteed that the safe stock will outperform the risky ones.

Buffett understands this intuitively. He invests in high-quality companies with deep moats and holds them for long periods. He has stayed invested in Coca-Cola for 37 years, American Express for 30 years, Geico, and See’s Candies for more than 50 years.

“Our favorite holding period is forever” — Warren Buffet

No Fees

The unique structure of Berkshire Hathaway allows investors to pay zero management fees. Buffett has repeatedly highlighted that if Berkshire had charged even a standard 1% investment management fee, shareholders would have spent billions in fees.

Incidentally, if Berkshire Hathaway had paid just 1% in investment management fees last year, it would have cost $8B— for something we didn’t really need help with.

Investment management is a very good game — because you charge fees whether you perform well or not, and even more if you do perform well. It’s a well-designed business for those who practice it — Warren Buffet

In his 2016 annual letter to shareholders, Buffett tells the story of his $500,000 open bet: “No manager can choose a set of at least five actively managed funds that would beat the Vanguard S&P 500 index fund after fees, over one decade.”

Ted Seides was the only person who answered the call, and he selected five funds-of-funds.

Despite a neutral market environment and the substantial financial incentive to do well, the five funds averaged 2.2% in returns against the index fund’s 7.1%. And this was even before fees were considered - 60% of all gains were diverted to the two levels of fund managers!

Buffett ended by saying some competent managers justify their fees, but the problem is finding them among the thousands.

Epistemic humility

The biggest winner in Buffett’s 8-decade-long career came in his last decade. Buffett was never big on technology bets. He was a flip phone user when he started investing in Apple. He accurately identified Apple’s hold on its customers and how his grandchildren were iPhone devotees.

Imagine the humility required to change your mind in your mid-80s about technology and making it your biggest portfolio position in a few years.

Berkshire spent ~$31 billion over the next few years, acquiring ~5% of Apple. Apple went on a tear and rose by more than 700% in the next 7 years. By the end of 2023, just this one position had grown to over $175 billion, representing an unrealized gain of $140 billion.

I’m somewhat embarrassed to say Tim Cook has made Berkshire a lot more money than I’ve ever made — Warren Buffet

And a little bit of luck

Buffett is quick to acknowledge the luck that played in making him the greatest investor of all time — he was born in 1930 in the United States right at the end of the Great Depression, was exposed to stocks as a child because his father was a stockbroker, was able to benefit from an era of free money in his prime, and studied directly under Benjamin Graham in the company of competitive peers.

In his own words:

“My wealth has come from a combination of living in America, some lucky genes, and compound interest… In an economy that rewards someone who saves lives of others on a battlefield with a medal, rewards a great teacher with thank-you notes from parents, but rewards those who can detect the mispricing of securities with sums reaching into the billions.”

Check these out:

If you have made it this far, chances are you have gained at least a few insights to help you become a smarter investor. If you would like to receive reports like this frequently and get access to our complete research, consider becoming a paid subscriber! Thank you :)

Footnotes

Source: Buffett’s Alpha (Frazzini et al)

Extremely insightful!

Fascinating! I’m Harrison, an ex fine dining industry line cook. My stack "The Secret Ingredient" adapts hit restaurant recipes (mostly NYC and L.A.) for easy home cooking.

check us out:

https://thesecretingredient.substack.com