No Stock Left Behind

Countering concentration risk with an equal weight portfolio

Hi there,

Before we jump in, I would like to thank you for the overwhelming support we received for 930Alpha. The response was far better than I expected, and I will need ~2 weeks to onboard you to the platform. Look out for an email from our team, and appreciate your patience :)

At the root of all financial bubbles is a good idea carried to excess — Seth Klarman

The Pontiac GTO was an icon: a roaring 348-horsepower declaration of American swagger. When Steve McQueen dodged Boston cops in the ‘Thomas Crown Affair’ in a 1967 GTO, it became a cultural symbol of the American auto industry. Every single GTO rolled off assembly lines in Detroit. It embodied ‘Motor City’ at its peak: when Detroit ruled the global auto industry and its engines powered the nation's dreams.

Detroit was the fourth-largest US metropolis, and ‘Detroit Muscle’ epitomized the golden age of American manufacturing: an era when every sixth paycheck in the country came from automakers.

Detroit’s success in the 50s was almost entirely tied to the Big Three (General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler). Their automotive plants helped build a strong middle-class tax base, which was the lifeblood of the Detroit economy, making it one of the wealthiest cities in the world.

The 70’s changed all that. The first crack in Detroit’s auto industry was the 1973 oil crisis, when gas prices quadrupled, and demand for thirsty muscle cars evaporated. By the 1980s, Japanese imports had stolen the spotlight.

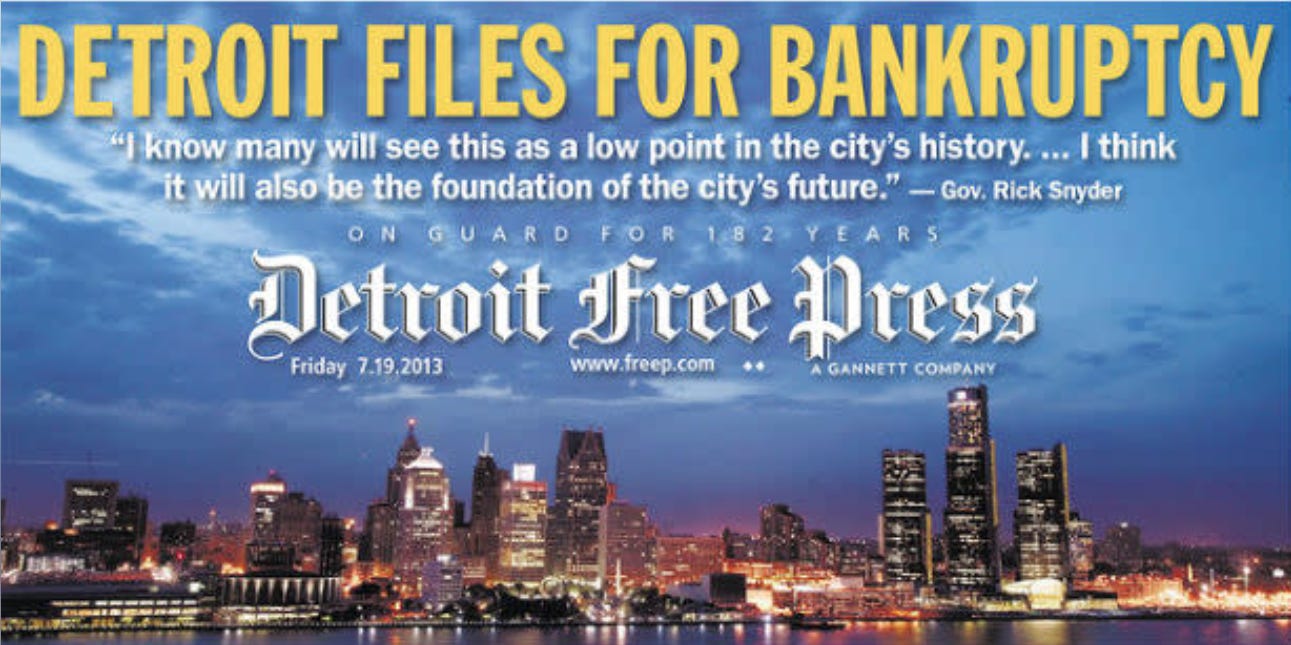

The 2008 crisis dealt the final blow: GM and Chrysler went bankrupt, and Ford had to mortgage everything, including its blue logo as collateral, to stay solvent (which they got back in 2012). Detroit itself filed for Bankruptcy in 2013: the largest municipal bankruptcy in history.

Detroit didn’t collapse because it bet big on cars; it collapsed because it never prepared for when building muscle cars wouldn’t be enough. The auto industry dominance wasn't a deliberate act - just an accumulation of small wins that eventually became a single point of failure.

When disaster struck the US auto industry, Detroit had no backup plan.

Today, the S&P 500 faces the same silent risk of overconcentration. We touched on this at the start of the year, when the top 10 stocks accounted for an incredible 38% of the S&P 500's contribution.

Most investors underestimate how top-heavy the S&P 500 really is.

Stick around a bit more for the answer. Even after the recent decline, the top 10 stocks still account for nearly 36% of the index, higher than during the tech bubble.

This is not a flaw; it's the system working exactly as designed. Market-cap weighting automatically allocates more investment to the largest companies. Like Detroit, the danger isn't in the strategy - it's in not recognizing the concentration until it's too late.

Coming to the poll you just took, if you were to invest $100 in the S&P 500 today, only $2 would go to the bottom 100 companies.

The alarm bells regarding overconcentration have been ringing for quite some time, and a previously overlooked strategy is now gaining momentum: the equal-weight portfolio.

Why is it making a comeback now? More importantly, is it the silver bullet against concentration risk and hype fueled bubbles?