The Economics of the Second Trump Administration

When "America First" means "Experts Last"

The Montezemolo Effect

Ferrari was the most dominant team in F1 from 2000-2004, having won 5 drivers’ and constructors’ championships in 5 consecutive years.

Under the technical leadership of Ross Brawn, the design genius of Rory Byrne, and the team management of Jean Todt, the team operated with a cold, terrifying efficiency.

At the center of it all was Michael Schumacher, a driver so dominant he made the sport boring.

So much so that 20 years later, the record for the most championships still belongs to Schumacher (tied by Lewis Hamilton in 2020)

Those years were the most glorious years for Ferrari in F1.

But in the boardroom in Maranello (Ferrari’s HQ), Chairman Luca Di Montezemolo was unhappy.

He didn’t necessarily hate all the winning; he was just unhappy with who was doing it.

By the end of 2006, he had successfully forced Schumacher into retirement.

The politics within the team had finally begun the institutional rot.

What followed was an exodus of the very top management that gave Ferrari its best years.

Ross Brawn retired with Schumacher, Byrne moved on to a consultant role with significantly less involvement, and Todt slowly exited his role from 2007-09.

The results seemed fine at first.

Ferrari won the championship in 2007 with Kimi Räikkönen. The car was still fast; the momentum of the “Dream Team” era was still pushing them forward.

But the institutional rot finally caught up with the performance.

Ferrari started making critical strategic errors while getting outdeveloped by rivals like Red Bull and Mercedes.

And even on days when everything else clicked, they simply couldn’t sustain that form for a full season.

It was like a massive game of whac-a-mole. Fix one thing, and something else would go wrong.

It has been 18 years since Ferrari’s last championship.

The most prestigious, well-funded brand in the world has spent nearly two decades watching more efficient, meritocratic teams drive past it.

All of this, because the leadership couldn’t do what’s best for the team.

Then and Now

As we analyze the economic roadmap of the second Trump administration, it is imperative that we first focus on the state of the economy.

While Trump has declared that the economy is the healthiest it’s ever been, it’s worth taking a look at what’s actually happening.

The Whac-a-mole Economy

Tariffs

In the first eight months of the second Trump administration, there have been so many tariff policy announcements that it is difficult to even keep track.

A good resource to track every tariff movement can be found here.

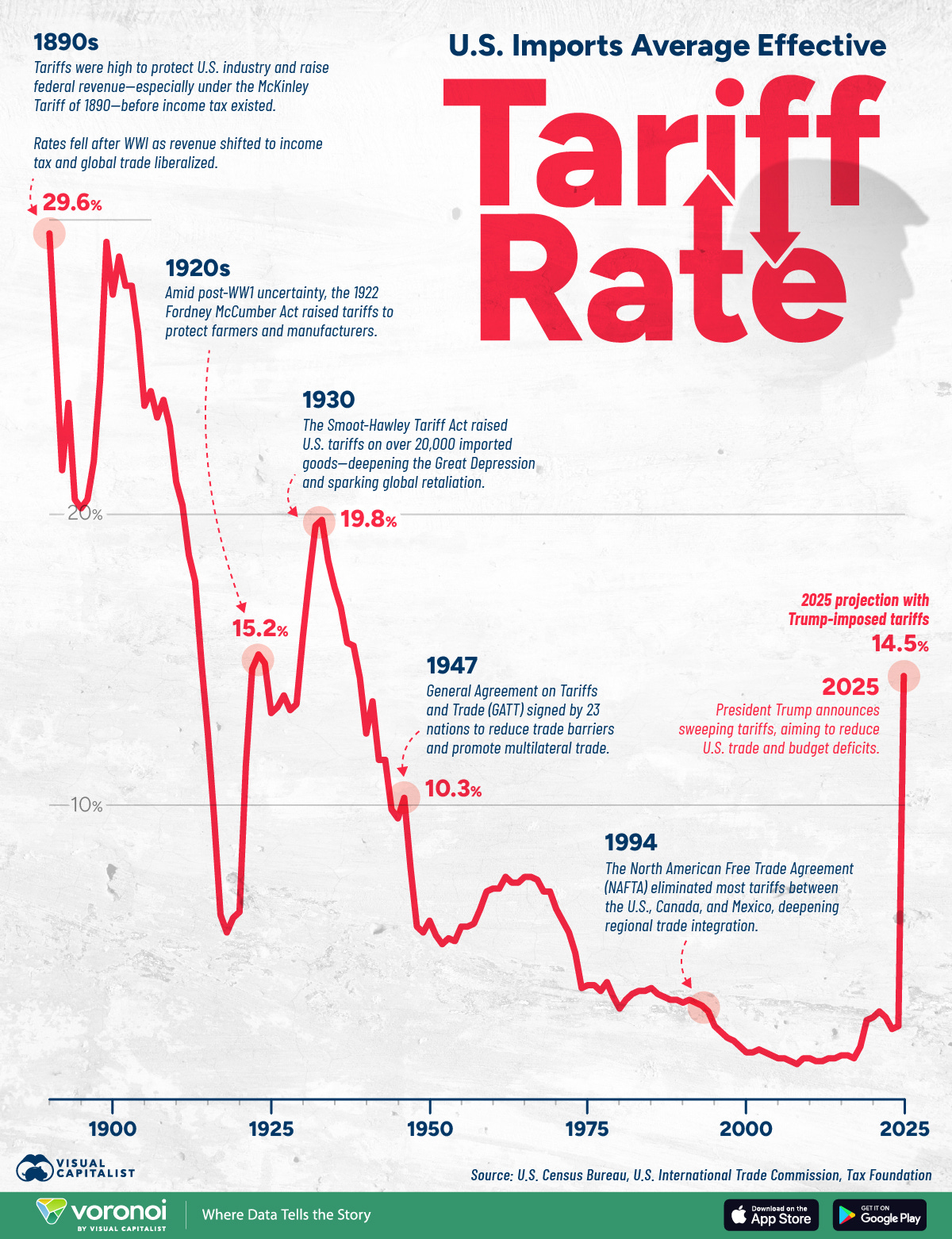

At present, average tariff rates are far higher than they were at the beginning of the second Trump administration, standing at about 17%, the highest since 1935.

For reference, the average tariff rates for the last 50 years have mostly remained under 4%!

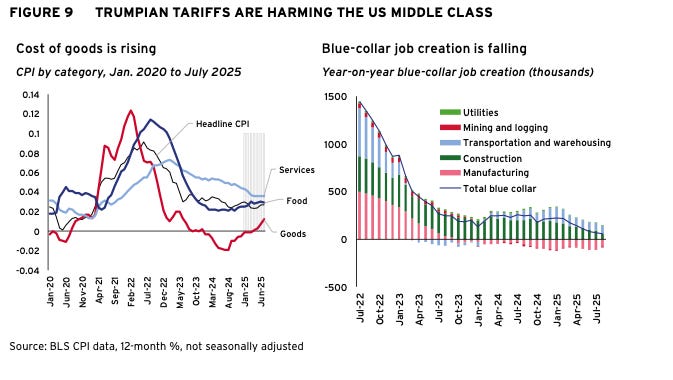

The immediate rise of tariffs from the period of ‘mellow’ in the last 50 years has had significant effects on the U.S. middle class.

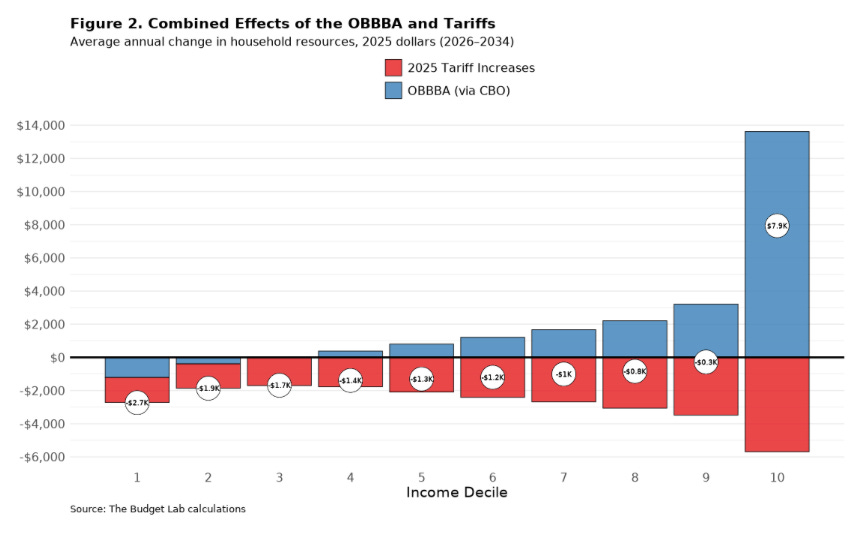

As of September, estimates of the cost for a typical household due to tariffs and the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) are in the thousands of dollars.

Only the top 10% of households are expected to walk away with a net positive.

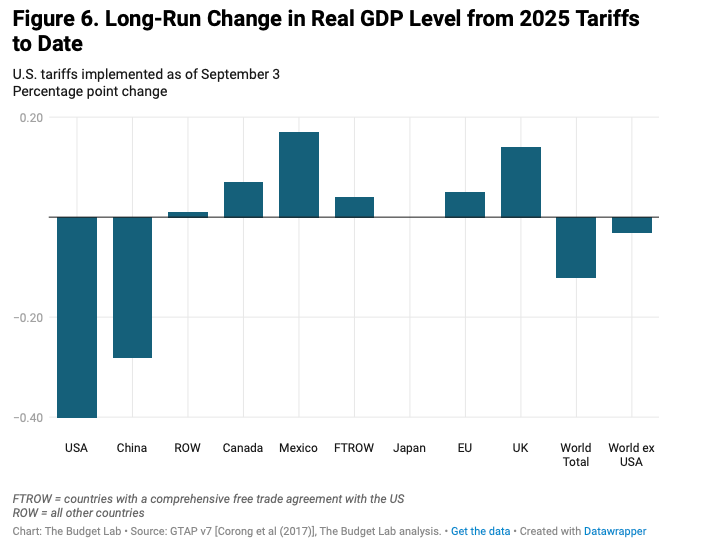

The tariffs are established to be a net negative for a typical household in the U.S., but how does it affect the GDP of the country?

The tariffs aren’t a net positive in any way, shape, or form. In fact, tariffs are estimated to continue losing revenue as the years go by.

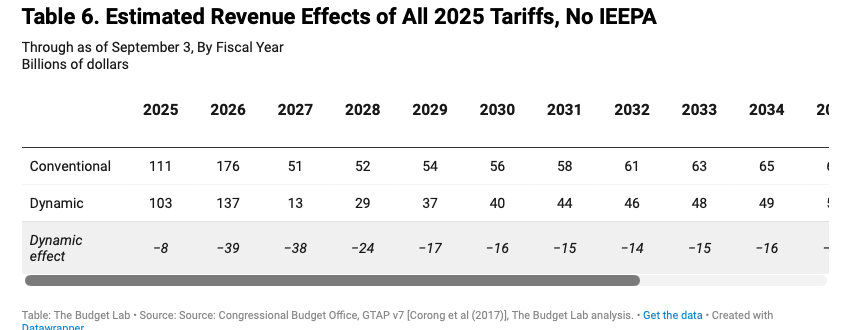

Here’s the estimated revenue effects of all tariffs this year, and a projection for the future:

The ‘Conventional’ accounting (assuming businesses and consumers will continue buying normally even after tariffs) promises a windfall.

Now look at the ‘Dynamic Effect.’

This measures the macroeconomic damage.

When taxes/tariffs go up, businesses invest less, consumers spend less, and the overall economy slows down.

This row quantifies how much revenue is lost due to that slowdown, and it is consistently negative.

Inflation and other economics

The erosion of the U.S. economy comes at a time of sticky inflation, uncertainty about growth, and an AI-fuelled capital spending boom.

Inflation remains a key uncertainty after the pandemic, constantly at ~3%.

Add to that the tariffs that inherently push the prices to the consumers, and you’ve got a crisis -