No regrets

Investing to minimize future regrets

We had a chat with a few of you over the past few weeks, and you all seemed to love our stories. So, we have compiled a selection of great stories that are fun to read whenever you have time to kill – giving you a healthy alternative to doomscrolling on social media. Let us know what you think in the comments.

We are publishing this article without a paywall. Please share widely.

From a young age, Jeff Bezos was identified as “most likely to succeed” – he was an outstanding student, his high school valedictorian, and a National Merit Scholar. He graduated summa cum laude from Princeton. He had job offers from Intel and Bell Labs, but he chose to join a mathematical hedge fund named D.E.Shaw where he became a senior vice-president by 30.

But in 1994, Bezos read that the internet was growing by 2,300% a year. Continuing on his well-set path to comfortable wealth was a no-brainer, but he wanted to make a bet on starting an online bookstore. He eventually did start that bookstore, which became Amazon – but how does one take that sort of leap?

Bezos described his “regret-minimization framework” as follows:

So I wanted to project myself forward to age 80 and say, “Okay, now I’m looking back on my life. I want to have minimized the number of regrets I have.” I knew that when I was 80 I was not going to regret having tried this. I was not going to regret trying to participate in this thing called the Internet that I thought was going to be a really big deal. I knew that if I failed I wouldn’t regret that, but I knew the one thing I might regret is not ever having tried. I knew that that would haunt me every day, and so, when I thought about it that way it was an incredibly easy decision.

The beauty of this approach is that there are no recommendations on the “right” thing to do and no universal method of cost-benefit analysis. If you projected yourself to age 80, the regrets you would see would depend entirely on your own value system. Keeping that in mind, let’s explore how this applies to investing and how you can make better investment decisions that your future self wouldn’t regret.

A sure $100k or a risky billion?

Here’s a thought experiment. You can enter into a lottery where you can pick one of four options:

Based on our educated guess, the average Market Sentiment reader is decently well off – so even though there’s a guarantee of $100,000, we’re guessing that a lot of you would take a risk on the $1 million or $10 million bets that would be life-changing. The marginal utility of these options is higher, even if they’re slightly more risky. Now imagine that the chances of winning the other prizes dropped. How would you vote now?

Now, more people would stick to the “safer” option of $100,000 because as the chances of winning the higher prizes reduce, you risk regretting your decision to let go of a sure shot. Even in this case, someone like Elon Musk might gamble on the 10% chance of a billion because the other options wouldn’t move the needle for him. He has nothing to lose and everything to gain, because of the marginal utility, as we discussed in last week’s article on “The Devil’s Card Game”.

This thought experiment applies to investing as well. Investing is all about allocating your assets to opportunities, and your regrets influence the trade-offs you make. “Experienced regret” that comes from past investing decisions can shape your investment choices. Malmendier and Nagel did a study that showed how older and younger investors allocated assets to the stock market differently, based on their life experiences.

Despite one of the longest bull markets in history in the 50s and an upward trend, throughout the 60s, the older generation stayed away from the stock market. But remember that this was the generation that had started working during the Great Depression, something that left a mark on their minds lasting more than 30 years! The same could be true in the case of Japan - After the crash of 1989, the market has not regained its pre-crash peak so far. 50% of the financial assets in Japan were held in cash in 2018.

Due to the anchoring bias, the first experiences of people have undue weight in their own minds. Like Morgan Housel says,

“Your personal experiences with money make up maybe 0.00000001% of what’s happened in the world, but maybe 80% of how you think the world works.”

Exiting at the top

Glauber Contessoto struck a lottery that most people only dream of. He used all of his life’s savings and credit card debt to buy Dogecoin in 2020 – and turned $250,000 into $3 million in less than a year. He went viral and appeared on many podcasts, whose hosts desperately urged him to sell, but Glauber said he was in it for the long haul. Then, Dogecoin crashed, and by August 2023, his portfolio was worth only $50,000 – one-fifth of his original investment.

While “diamond-hands” is a sentiment most strongly associated with crypto, it’s something other investors do unconsciously as well. The investing adage is to let your winners run and cut your losers quickly – but most assets historically revert to the mean, which means overvalued assets tend to underperform, undervalued assets tend to outperform, and it’s impossible to tell in advance which is which.

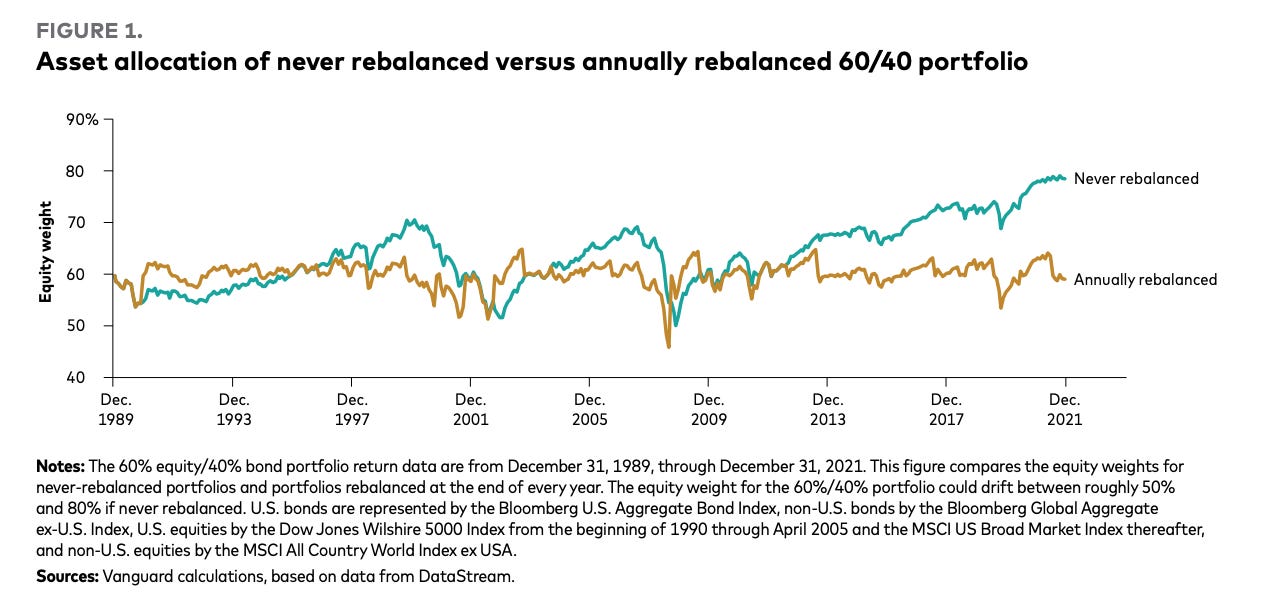

Rebalancing is one way to minimize regrets. By having a systematic plan in place to sell outperforming assets, either based on a threshold or a schedule, you cut down the risk of having the majority of your portfolio invested in one asset. We have covered different rebalancing options here, but the actual ratio of asset allocation matters less than the intent to stick to the plan.1

Diversification isn’t a magic pill. As Ben Carlson writes, investors in 2013 regretted not having their entire portfolio in stocks. In 2014 these stocks crashed, and they regretted going all-in. Regrets are omnipresent, but diversification is a policy of accepting that some regret is always inevitable and planning accordingly.

What will you regret?

Jeff Bezos’s framework is usually interpreted as a reason to take more risk and be bold. But that’s not the point – the exercise is to evaluate what your personal risk tolerance is, what your long term goals are, and how the two might be at odds. More conservative investors might realize that they would be okay taking a bit more risk to avoid future regrets. Aggressive investors might realize that they’d regret not playing it safe.

We’ll leave you with a thought experiment that we were discussing at Market Sentiment: We were discussing our own regrets, that our ancestors hadn’t started a business that had grown to millions of dollars, or invested in real estate when it was cheap. How could our parents have passed on Apple stock when it was selling for so cheap? But we realized the paradox here: There are probably undervalued opportunities (or investment behaviors) we are ignoring, precisely because they seem unattractive, and our grandchildren might regret our folly. On the flip side, we might be making investments now that they would deem unwise.

So what investment decision or omission do you think your grandchildren would regret, 50 years from now?

Hey there! If you’re a free subscriber, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Paid subscribers get thrice the number of articles, with in-depth deep-dives that bring you the best of academic and industry research for a fraction of the cost (Here is what subscribers are saying.) Even one expert insight here would pay for your subscription multiple times over.

Footnotes

Even Harry Markowitz, who won the Nobel Prize for developing modern portfolio theory and developing models for optimal asset allocation had this to say:

I should have computed the historical co-variances of the asset classes and drawn an efficient frontier. Instead, I visualized my grief if the stock market went way up and I wasn’t in it–or if it went way down and I was completely in it. My intention was to minimize my future regret. So I split my contributions 50/50 between bonds and equities.

Had to laugh, am already 80.

Hmm... Think I should buy some Bitcoin now. I have a feeling that my kids are going to ask me why I didn't buy it when it was cheap. Who knows.